The Netherlands During the Cold War: An Ambivalent Friendship and a Firm Enmity

The Cold War caused quite some fear in the Netherlands. Maybe not right after the end of the Second World War when the Dutch population was preoccupied with rebuilding the country after five years of devastation. Poverty was the main enemy in these first years, and the fear of a reviving Germany. However, after the Berlin Blockade in 1948 and the overthrow of the Czechoslovakian government by the Soviets in the same year, the fear of the Communist enemy grew. The callous crush of the Budapest uprising revealed the seriousness of the eminent threats upon the Netherlands. Dutch foreign policy dangled between protecting its interests in their disengaging colonies and defending against new threats. The Dutch found the United States against them while it was finding a new relationship with its former colonies. At the same time they underestimated the indispensability of the United States as a leader of the Western bloc.

How the Cold War Arrived in the Netherlands

The Second World War made it clear to everyone in the Netherlands that pre-war foreign policy needed to be changed. Before Germany invaded the Netherlands in 1940, the Dutch relied on its neutral position in Europe. This position was based on the assumption that the balance of power between the United Kingdom, Germany and France would prevent any of these Great Powers from invading the Netherlands. After all, none other powers would grant another Great Power permission to acquire the Netherlands. It also became clear that the last line of Dutch defense: inundation of polders became practically worthless after the introduction of air force as a main military operation.

Already during the Second World War the United States proved to be the strongest nation in the world not only militarily, but economically as well. The Soviet Union posed itself as the other world power, whereas the European Great Powers had to acknowledge that their dominion had severely decreased.

Dutch neutrality had to be discarded. Instead, the Netherlands had to adopt a new foreign policy reckoning with the new balance of power. Clearly the Dutch were not keen on leaning towards the Soviet Union. Before the War broke out, the Dutch were very disapproving of the Soviet Union and of Communism in general. The critical attitude toward Communism was somewhat mitigated because of the eminent role Communists played in the resistance against the Nazis. This gave Communism and the Communist Party of the Netherlands (CPN) some credits. In the first parliamentary elections after the Second World War in 1946, the CPN got more than 10% of the seats in the Second Chamber. Never before and never again, would they have such massive support. Despite lenience toward Communism in the first years after the War, the preponderant feeling was that the Dutch had to rely on an Atlantic orientation, focusing on United States leadership. Parallel to this Atlantic orientation, the Dutch invested in European economic cooperation as they became one of the six founding fathers of European Integration.

Right after Germany and Japan were defeated there was no necessity for a coalition between the United States and the Soviet Union. The conflict of interest and the ideological contradistinction between the superpowers became increasingly apparent. Europe was divided into two spheres of influence with an Iron Curtain in between. The introduction of the Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program) cemented the Netherlands distinctively into the western sphere of influence. In total the Dutch received more than 1,100 million dollars in aid from the United States. This economic assistance in addition to Dutch gratitude for the American role in liberating the Netherlands from the German occupation formed the basis of a long-lasting alliance.

The Berlin blockade of 1948 and the overthrow of the democratic government in Czechoslovakia by Communist one-party rule in the same year led to an increased fear of Communism in the Netherlands. Indeed, it fostered the support for the Treaty of Brussels as a bulwark against the Communist threat and it was a precursor to NATO in which the Netherlands participated since its foundation in 1949.

Protection Against the Red Threat

NATO was the main line of defense for the Netherlands ever since its foundation in 1949. The Netherlands seemed to have no problems with the leading role the United States took right from the start. Within the Netherlands there had not been much discussion about joining NATO. With the exception of CPN all political parties supported ratification. The fact that the Dutch defense was now embedded in a North Atlantic defense strategy did not mean that there were no disagreements.

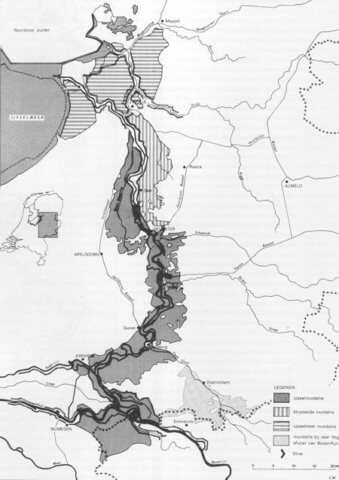

The United States had decided in the late 40s that the western allies would not be able to hold off the Red Army in case they would start a conventional attack. Therefore, the U.S. proposed a strategy of “Peripheral Defense.” This implied that the allied troops would gradually retreat behind the Rhine, and hold out until the moment the Red Army arrived. Conventional warfare would be avoided by a further retreating to the United Kingdom. The Netherlands did not want to sacrifice the entire country and thought that an alternative defense line had to be developed. In 1951 the Netherlands, therefore, started to build the IJssel-line: a large scale waterway infrastructure project using the well-tried technique of inundation. The idea was to dam the main rivers Waal and Neder-Rijn in case the Red Army attempted to undertake a conventional attack. By damming the main rivers, the water could be pushed through the river IJssel leading to the IJsselmeer. The river IJssel unable to absorb the enormous amount of water, would flood. The infrastructural project would imply numerous landscape interventions like dikes and inlets to materialize expanses of water of the right depth: on the one hand not too shallow so as to prevent tanks from crossing, on the other hand not too deep so as to prevent ships from sailing across.

The Soviet Union soon found out about this new defense structure while the large majority of the Dutch population only learned about the IJssel-line long after it was dismantled in the early 1960s.

An Ambivalent Relation with the United States

The standard characterization of the Dutch post-war foreign policy is that they were very staunch allies of the United States. A good example of this is the information movie by Kees Stip that was broadcast by the Dutch Government in 1955. The movie was called: “Wij leven vrij” (we live in freedom). In a somewhat cynical tone it holds up the fundamental differences between the Netherlands as a free country and “certain other countries” evidently referring to the Soviet Union and its satellite states. At the end of the movie the conclusion is that the western countries had to unite to fight this threat explicitly referring to the Brussels Treaty and NATO. It also calls for understanding the need for major and long-lasting sacrifices for funding the military obligations the country had as a NATO-member.

Already from the start of NATO the Dutch share in NATO’s defense expenditures was relatively high compared to that of other smaller member states. Furthermore, the Dutch always showed themselves as an opponent to the development of an European defense organization apart from NATO as wished by some of large European nations. Rather, the Netherlands focused on a strong Atlantic alliance and was even prepared to fully hand over the decision on a nuclear attack to Washington. The Dutch were also one the few nations that supported the United States in the United Nations operation during the Korean War.

All this points at a high level of trust in the new forms of international cooperation like NATO in order to turn the Soviet threat. But at the same time a very ponderous relation arose with the United States.

Diverging ideas about colonialism formed the origin of this controversy. After World War II had ended, the Dutch were very keen on regaining control over their colony, Dutch East Indies. The Dutch thought that this colony was pivotal for their economy. The slogan “Indie verloren, rampspoed geboren!” (Indies gone, prosperity done) was extremely popular in the Netherlands and describes well how strongly the Dutch people thought about keeping control over their colonies.

In 1945, when Japan was defeated, the nationalist leader Sukarno declared independence.[1] In 1947-1948 the Dutch undertook military operations euphemistically referred to as “Politionele Acties”[2] in an attempt to regain control. The military operations were an enormous financial burden for the Netherlands. Furthermore, it led to an extremely isolated position since many countries disapproved of the Dutch position. The United States was very clear in criticizing the Netherlands and in supporting the Indonesian opposition. Moreover, the United States put much pressure on the Netherlands by linking the continuation of Marshall-help to their behavior in Indonesia. The Netherlands gave in to international pressure and agreed by signing the declaration of independence of Indonesia in 1949.

However, strife between the Netherlands and Indonesia continued even after the formal independence. One of the remaining conflicts was the status of New Guinea. The Netherlands refused to renunciate, which led an enduring diplomatic conflict with the United States[3].

The Dutch position even hardened in 1952 when Joseph Luns became one of the two Dutch Ministers of Foreign Affairs[4]. Luns took a tougher stance by emphasizing that the Dutch interests in the East should not be squandered. The public opinion abundantly supported Luns in this and shared his critical attitude towards the United States. The relation even worsened when Indonesia’s President Sukarno received a most exuberant reception in Washington when he visited the United States in 1956.

The Suez Crisis in 1956 again led to tension between the United States and the Netherlands as the Dutch chose sides with France and the United Kingdom. The United States heavily protested against the military operations carried out by Israel, the UK and France in Egypt as a reaction to Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal. The United States blamed France and the UK of acting in a neo-colonial way and pressured them to withdraw. After the Suez Crisis had ended, the lesson could be drawn that old colonial powers like France and the UK were unable to independently steer international conflicts without the United States’ consent. Throughout the conflict though, the Netherlands were staunchly at the side of the French and the UK. Reason for this outspoken position was the fact that the Dutch saw a clear link between what happened in Egypt and the developments in Indonesia. If nationalists like the Egyptian leader Nasser got their way with nationalizing assets, this would set the example for President Sukarno to do the same in Indonesia thereby harming Dutch interests.

1956: While Budapest Burns, the Communists are Dancing

Right at the moment the Suez crisis came to a climax, the Budapest uprising was crushed by Soviet troops. It became clear that the de-Stalinization process Khrushchev had started had clear limits. The Soviet Union did not allow its satellite states to disengage from the Soviet sphere of influence. The Hungarian intention to leave the Warsaw-pact was unacceptable for Moscow and led to a heavy-handed operation to restore the Soviet control over Hungary.

As in more West-European countries, this led to fierce indignation in the Netherlands. In several demonstrations many people loudly protested against Soviet actions. The anger of the protesters directed mainly toward the Dutch Communist party CPN and their newspaper, “De Waarheid” (truth). The sharpest clash occurred on the November 4, 1956. Protesters gathered in front of the Communist Center in Amsterdam, “Felix Meritis.” In this Amsterdam building not only the CPN had its base; it also housed the editors and the printing press of the newspaper “De Waarheid.” Right at the moment the protesters arrived, they could hear the music playing at the weekly dance-evening of the ANJV, an organization for young Communists. This infuriated the protesters even more: “While Budapest burns, the Communists are dancing!”

After a few days the protests against Communism mitigated, but generally the Dutch attitude toward Communism hardened. Communist representatives were politically isolated. For a while many non-Communist members of Parliament ostentatiously left the Second Chamber of the Parliament when a member of the CPN took the word. The events in 1956 also stopped Communism from being fashionable. Before 1956 there were several intellectuals, artists etc. who would pose themselves as Communists, but most of them distanced themselves from the events in Budapest and afterward stopped labeling themselves as Communists. Nevertheless, the hard-core members of the CPN entrenched themselves in defending the Soviet action against the reactionary anti-revolutionary forces in Budapest.

Despite massive indignation, there was not much the Dutch Government was doing to influence the international events taking place. It became clear that the Eisenhower Administration was not going to risk World War III over Budapest, regardless of their proclaimed strategy of Roll Back Communism. The Dutch government decided to boycott the Olympic Games in Melbourne taking place in that same year. Only two more countries (Spain and Switzerland) decided to do the same. Beside this boycott, however, there were no actions taken other than admitting approximately 3,400 Hungarian refugees into the Netherlands.

The Dutch government and its population came to the conclusion that the Red Threat was not to be underestimated. The events in Budapest showed the real face of Communism, and therefore precautions had to be taken. The Dutch civil defense organization “Bescherming Bevolking” (peoples protection) already established in 1952 took a more prominent role after 1956. More than 160,000 volunteers participated in drills and preparations for a possible attack by the Red Army. They focused on a nuclear attack. At that time, but even more afterwards there was quite some criticism about the real effect these actions would have in case of an attack. Perhaps the actions of Bescherming Bevolking primarily functioned as a comforter rather than an effective defense or rescue method.

Vietnam Protests in the Netherlands: Johnson Miller!

In April 1966 a protest song “Welterusten Mijnheer de President” (Goodnight Mr. President) written by Lennaert Nijgh and sung by a protest singer Boudewijn de Groot entered the charts. It is cynically addressed (to) President Johnson of the United States asking him if he slept well at night knowing what goes on in Vietnam. It became an extremely popular protest song and was a prelude to the massive protests against the U.S. war against North-Vietnam.

The Dutch government officially backed the United States in their Vietnam strategy, but never gave in to requests by the United States to send Dutch troops to Vietnam. The Dutch government and especially Minister of Foreign Affairs Luns had not forgotten about the American opposition in the debate about Indonesia. They surely were not keen on saving the Americans now in this other Asian country. The government kept an ambivalent attitude towards the United States.

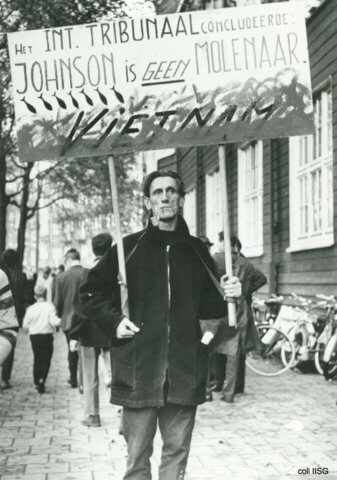

The Dutch popular protest grew; more people resented the Vietnam War and especially the role that the United States played in it. The protests against Vietnam coincided with the general protests by leftist people against the political establishment. A tide of political renewal changed the political landscape. New political parties appeared and the protest generation of the sixties made itself heard. The police did not know exactly how to deal with these protests. When protesters chanted that Johnson was a murderer, the police arrested protesters for insulting a befriended Head of State. Consequently, the protesters changed their slogan from Johnson Moordenaar (Johnson killer) into Johnson Molenaar (Johnson miller).[5] This confused the authorities who had a hard time adjusting to the 60s anyway. Despite the sometimes spectacular demonstrations and cultural manifestations, there was only a very limited influence on the general public. The demonstrations were relatively small scaled with no more than 15,000 people at its peak. Furthermore, in 1968 there was still a vast majority ( 65%) of the Dutch population who thought that the American presence in Vietnam was justified.

The second wave of anti-Vietnam demonstrations occurred in 1972 as a reaction to the “Christmas Bombardments” as they were called. On that occasion more than 50,000 people demonstrated against the Nixon Administration.[6] This second wave of demonstrations coincided with a new generation of Foreign Ministers. Luns had been the Foreign Minister from 1956 until 1971. Throughout these years, he embodied the ambivalence felt toward the United States. He had had fierce disputes with the United States about Indonesia, New Guinea and the Suez Crisis. At the same time, however, he was always very clear in his position that the Netherlands needed the United States as an ally. Despite the conflicts he had with the United States, he made it very clear that ultimately the Dutch would support them. This was also the reason for him to refuse more than once to convey the protest of the Dutch Parliament about the Vietnam War to the U.S. President. Luns’ successors at Foreign Affairs, Mr. Schmelzer and even more Mr. van der Stoel, changed the Dutch relationship with the United States. These Ministers were not very hesitant in voicing the Dutch Parliament’s widespread disapproval about Vietnam. Furthermore, the Social Democratic Minister van der Stoel alienated the Americans even more by the decision to provide development aid to countries, like Cuba, regarded as unfriendly towards the United States.

Rather a Russian in my Kitchen . . .

Despite President Carter’s original point of departure, the arms race increased during his Presidency. Around 1976 the Soviets had installed numerous SS-20 nuclear missiles on several missile sites spread over Eastern European countries.[7] These missiles were aimed at Western Europe. In 1979 NATO decided to deploy missiles in Western Europe in attempt to counter these Soviet SS-20 missiles. The NATO asked the Dutch government to allow missiles to be placed on the Dutch territory as well. The Dutch government had no objections, but the public protests were of an unprecedented scale, more than 550,000 demonstrators at its peak on October 29, 1983. More than 3.75 million people, a quarter of the population, signed the petition against the missile placements. These demonstrations did not necessarily protest against the United States, but more against the Dutch government blindly following a NATO-request, rather than listening to the its citizens. However, despite the criticism about the missiles deployment, the Dutch population still backed NATO-membership. Even in 1983, when the protests peaked, no more than 20% of the population favored leaving the alliance.

Contrary to the anti-Vietnam protests in the 60s and 70s, public opinion now deviated strongly from the position the government took. The massive protests resulted in a very long decision-making process. The Dutch consensus style prevented the Dutch government from simply making a decision against the will of a majority of the population, but on the other hand did not want to let down the other NATO-members either. They were particularly sensitive to the disapproval from the United States. The Dutch Government announced that they would need much time to make a final decision. The NATO granted the Netherlands 2 more years to come to a conclusion.

Domestically the decision about placing the missiles caused quite some political turmoil. Formerly, especially before the 70s, foreign policy had not been a prominent politicized issue. But more and more a distinction between “right” and “left” positions emerged when it was about foreign policy. The “right” political parties inclined toward warm relationships with the United States and strong support for NATO, whereas the “left” political parties were far more critical of the Atlantic alliance. This demarcation line sometimes even split political parties, like the Social Democratic party where the more Atlantic oriented members fiercely disagreed with the more progressive wing. Within the newly merged Christian Democratic Party the conservative party line clashed with the more evangelical branches linked to the Peace Movement. Ever since the 70s the Parliament took a more proactive role in the foreign policy of the Netherlands.

Beside the heated discussions in the political discourse, it also had its manifestation on a cultural level. Protest singer, Armand, wrote a song in which he proclaimed he would rather share his country with the Russians (Soviets) than live in a garrison state. His slogan “Liever een Rus in m’n keuken dan een raket m’n tuin” (rather a Russian in my kitchen than a missile in my back yard) was often used in the numerous peace-demonstrations in the 80s. Then by the end of 1982 pop group “Doe Maar” had a number 1-hit with “De Bom” (The Bomb) with the underlying message: What’s the point of making a career, doing your homework when a nuclear bomb can drop at any moment?’ These songs reflect the grim world view many people tended to have those days because of the dead-end arms race taking place between the super powers. The hit “Over de Muur” (Across the Wall) by “Klein Orkest” in 1986 points at the absurd division of Berlin by a wall and claims that both sides are kept hostage by their own system. In most of the cultural expressions of the eighties, the anger and incomprehension did not focus on the Soviets as the declared enemy but rather on the undefined systems that kept the Cold War going on. Songs and other cultural outlets, express the fear that mankind will not be able to control the enormous and ever increasing armory which one day might destroy us all.

Nevertheless, public opinion surveys show that in the late 70s and 80s nuclear weapons and East-West relations in general had little priority.[8] Domestic problems in the field of social and economic policy scored (a) far higher on the list of priorities.

Due to this complex domestic debate, two years were not enough to find a consensus in the Netherlands. This frustrated the other NATO-members who called this inability to make a decision “Hollanditis.” Finally, Ruud Lubbers, the Dutch Prime Minister at the time, came up with the solution: the Netherlands would reject the NATO missiles in case the Soviets did not increase their number of SS-20 missiles by 1 November 1985. Only if the Soviets had increased their number of missiles, the Netherlands would have placed the cruise missiles. This led to disbelief and incomprehension among the western allies as this meant that it was now Moscow who would decide if the Dutch would place NATO-missiles or not. Thanks to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty signed by Reagan and Gorbachev in 1987 the missiles were never actually placed.

By the time it became clear that the Eastern European nations were disengaging from the Soviet Union (1989) succeeded by the implosion of the Soviet Union itself (1991), the Netherlands was solidly back to its irrefutable Atlantic orientation. Once more the Dutch posed themselves against a European defense organization loose from NATO. This was a prelude to the Dutch foreign policy in the post-Cold War period.

Conclusion: A Policy of Fear

One main characteristics of the Cold War was that it divided the world into two spheres of influence. Throughout all the Cold War years it was clear that the Netherlands always belonged to the western camp, with the United States as its hegemonic leader. Nevertheless, this did not mean that the Netherlands uncritically followed the United States in all cases. During the period right after World War II until the beginning of the 50s, there had been many serious disputes about the decolonization of Indonesia and New Guinea, and about the position the Dutch took in the Suez crisis.

However, these disputes were always overshadowed by a more serious hazard: the threat of a Red Army invasion. For the Dutch it was very clear that without the support of the United States Europe was defenseless against the Soviet Union. Therefore, the Atlantic Alliance was indispensable. Additionally, the good relationship with the United States was also supportive for the power balance in Europe. Logically, a small nation like the Netherlands was afraid of domination by the great European powers. In respect of this, a powerful friend overseas was most instrumental. Lastly, the Dutch never forgot their gratitude toward the Americans for playing a pivotal role in liberating their country in World War II and for their Marshall Help.

Through the years, the fear of a Communist conquest increased and with it the fundamental choice of the Western camp, while the consensus about Dutch foreign policy decreased. From the 70s onward, the Dutch foreign policy became a domestic political issue. Discussion about the Atlantic Alliance mounted, and the discord split the public and it even split political parties. Nevertheless, even during the peak of protests against the placement of missiles in 1983, the public support of the Atlantic Alliance was never fundamentally questioned by the majority of (the) population, not even by the sizeable minority.

At times the Dutch government must have signed for the complex decisions that had to be made concerning their foreign policy. But the real foreign policy brain twisters emerged only after Moscow stopped being a conceivable threat to the West. It then became clear that the Dutch foreign policy throughout the Cold War had been guided by fear: fear of the Soviet Union, and that new guidelines had to be found or developed for the Post Cold War period.

Notes

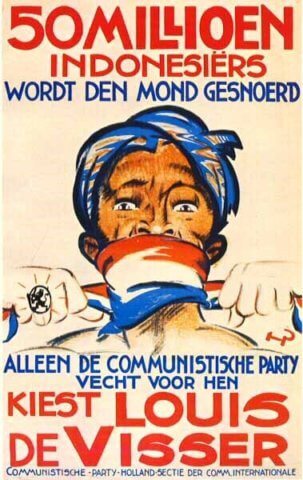

1. Cartoon is poster for the Dutch Communist Party (CPN) protesting against the Dutch policy concerning Indonesia. CPN was the only Dutch political party protesting against this. The poster says: 50 million Indonesians are silenced, only the Communist Party fights for them. Vote for Louis de Visser.

2. The term “Politionele Acties” could be translated as “police actions.” This term is euphemistical because in fact there were many tens of thousands soldiers—not policemen—fighting the Indonesian Republican Troops.

3. The dispute about New Guinea dragged on till 1962, when it became part of Indonesia.

4. In 1952, the Netherlands had two Ministers dealing with foreign affairs. Beyen mainly focused on European politics, whereas Luns would take care of Atlantic affairs and former colonies. Reason for this unique construction was the fear of some parties that European politics would be dominated by Catholics only. Therefore they did not want the Catholic Luns on that post. Consequently Beyen was added to the team as a non-partisan.

5. The photo shows a man walking with a sign post which reads: The Int(ernational) Tribunal concluded: Johnson is no miller.

6. Some estimates even assume there were up to 100,000 protesters participating in the demonstrations.

7. This poster was designed by cartoonist Opland and became a symbol for the Anti War Movement. It says: The Hague, October 29. No new cruise missiles in Europe.

8. Eichenberg,C. The Myth of Hollanditis, in International Security 1983 (Vol.8, No.2) referring to NIPO-surveys for public opinion 1977 to 1982)

Also available are “Enemy Images, Evidence, and Cognitive Dissonance: The Cold War As Recalled by Michiganders“; “The American Perspective of the Cold War: The Southern Approach (North Carolina)“; “Soviet Perspective on the Cold War and American Foreign Policy“; “The Polish Perspective of American Foreign Policy: Selected Moments from The Cold War Era“; “The Special Relationship: United States-Russia“; “The U.S. Foreign Policy Establishment’s Perception of Poland (1980-1981)”; “After the Cold War: U.S.-Ukrainian Relations (1991-2000)“; Soviet Attitudes Towards Poland’s Solidarity Movement” and “The Paradox of Solidarity from a Thirty Years Perspective.“

This was originally published with the same title in Comparative Perspectives on the Cold War, Lee Trepanier, Spasimir Domaradzki, and Jaclyn Stanke, ed. (Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski Krakow University Press, 2010).