Camus’ Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism

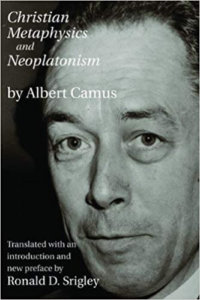

Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism. Albert Camus with Ron Srigley, trans and introduction, and Rémi Brague, epilogue. South Bend, IN: St. Augustine Press, 2015.

Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism is an important contribution to the study of Camus as well as to the disciplines of religion, philosophy, literature, and political theory. In addition to offering a fresh and literal translation of this neglected but critically important work by Camus, Ron Srigley also provides an introduction that places the work in the context of Camus’ life and thought. Srigley also reviews the scholarship on Christian Metaphysics and shows how his translation and interpretation of the book fits into this literature. The book concludes with an epilogue with Rémi Brague that takes issue with Camus’ account of Christianity. For those who read and study Camus, and even for those who do not, Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism is required reading as an entry point to one of the most original and influential thinkers of the twentieth century.

Srigley’s translation of Camus’ Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism is the second one in the English language. The first translation is Joseph McBride’s version that was published in 1992. According to Srigley, his translation aims at more literalness than McBride’s because:

“. . . a faithful translation will not try to smooth over the bits that jar or seem unfamiliar, but allow them to stand in order to test the reader’s patience and stretch his imagination in the hope that some unsuspected corner of the original text might be revealed” (12-13).

Besides being more literal, Srigley’s translation expands on McBride’s clarification of Camus’ biblical citations by tracking down Camus’ other unidentified sources and offers a proper titles and references for them. Srigley also shows in his notes how the ideas and arguments of Christian Metaphysics unfold in Camus’ subsequent works, revealing the importance of this book for Camus’ mature thought.

Finally, McBride’s translation does not present Christian Metaphysics in the broader context of Camus’ works or explain its influence on them. Srigley corrects this fault not only by offering an informative introduction about Camus’ life and thought and the critical role that Christian Metaphysics plays in them, but also by providing a review of the scholarship on this work: McBride’s interprets the work in the context of Camus’ idea of the absurd; I. H. Walker explores Camus’ use of Plotinus’ Enneads; Jacques Hardré looks at the argument and structure of Christian Metaphysics; and Paul Archambault explores the book as a way to understand and judge the character of Camus’ Greek culture.

In his introduction Srigley illustrates his points of agreement and disagreement with these interpretations. For Srigley, the book is significant because it shows Camus’ abiding concern with the relationship between Christianity and Classical Greek Civilization that appears in his later works. Although Christian Metaphysics was Camus’ thesis for his university degree, its theme was revisited by Camus throughout his career: the relationship between Christianity and Greek civilization.

The first chapter, “Evangelical Christianity,” examines biblical texts and the works of the early Church Fathers to demonstrate the novelty of Christianity in relation to the classical world. Camus explores Gnosticism in the second chapter, “Gnosis,” where he argues that Gnosticism was not an exclusively Christian phenomenon but rather an attempt by both pagan and Christian thinkers to reconcile reason with the belief of salvation. The next chapter, “Mystic Reason,” is an analysis of Plotinus’ Enneads in which reason and salvation are reconciled within the tradition of Greek philosophy.

The final chapter, “Augustine,” argues that Augustine’s Christian synthesis of Hellenism and the Gospels was more successful than that of the Gnostics because he relied upon Plotinus’ work. By conceiving of reason as participatory, Plotinus made Greek reason more acceptable to Christian faith. Augustine, in turn, used this understanding of reason to make Christianity more suitable to Greek and Roman pagans. The result was a Christian metaphysics that had a universal appeal in the Mediterranean world.

For Camus, the great novelty of Christianity is not faith, because faith only shields Christian beliefs from criticism, but rather the Christian notion of apocalyptic history and a final redemption in the afterlife. This belief in the apocalypse expresses a tragic sensibility in which the Christian embraces his or her mortality in the hope of redemption. Yet this path to redemption also empties the world of meaning, unlike the Greeks who recognized the divine but also the significance that the world possesses. Throughout Christian Metaphysics, Camus approaches each tradition from the other perspective and points out their assumptions and contradictions. Thus, Christian Metaphysics was the first step in Camus’ intellectual journey, a journey that culminates in mature works like The Rebel and The Myth of Sisyphus in which Camus returns to an exploration of the relationships between Christianity, Greek Civilization, and modernity.

Srigley argues that in The Myth of Sisyphus Camus is critical of the Christian and modern apocalyptic aspirations which he formulated as the absurd. Yet without a sense of the apocalyptic, the absurd descends into nihilism, making morality groundless and therefore meaninglessness. Throughout The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus alternates between the position of rejecting apocalyptic aspirations and recognizing their importance as a measure of truth. These contradictions continue in The Rebel where, according to Srigley, the two histories of antiquity are presented and contradict each other: the Greek and the Christian. For the Greek, modernity and Christianity are one and the same and therefore hope only resides in Greek Civilization as an alternative to modernity; for the Christian, its religion is the most effective alternative to modernity because it is the only tradition to have overcome the metaphysical rebellion and the problems of evil and death on which modernity rests.

Rémi Brague contributes his own thoughts about Christian Metaphysics in the Epilogue (translated into English by Srigley). Brague criticizes Camus’ analysis of Christianity because Christ “is paradoxically conspicuously absent” in the work (136). Brague claims that Camus’ failure to incorporate the person into his analysis makes Christian Metaphysics a flawed work. For Brague, the person is the one that is able to synthesize the insights of both Christianity and Greek Civilization, a concept that Camus neglects.

It might be a little unfair to criticize Camus for not addressing the concept of person in a work with the word “metaphysics” in its title, but Brague’s critique provides an interesting entry point to interpret the work in relation to the others in Camus’ oeuvre: is it best to demonstrate the development of an author’s work from his or her early works and those that come later, or is do we demonstrate the deficiencies of the early works from the vantage point of the mature ones? Which account best reveals the author’s thought and his or her development? I do not claim to know the answer to these questions, but the fact that Camus’ early work provokes them is a testament to the originality of his thought and enduring influence he has on thinkers today.