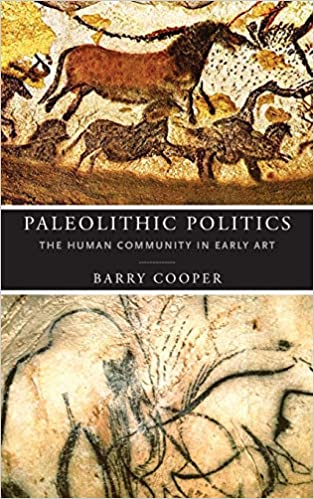

Paleolithic Politics: The Human Community in Early Art

Paleolithic Politics: The Human Community in Early Art. Barry Cooper. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2020.

Voegelin’s argued that ancient civilizations, like the Babylonians and Egyptians, depicted their empires as smaller versions of the cosmos. In Paleolithic Politics: The Human Community in Early Art, Cooper pushes Voegelin’s contention back to the inception of human consciousness itself, something into which Voegelin himself began to look. When Voegelin heard Marie König’s lectures about the paleolithic in the late 1960s, he was taken with her ideas and afterwards led him with her to explore rock formations and caves in the search of the beginning of human consciousness. König believed that early artifacts arranged in certain ways revealed a consciousness of time and space. For example, the burial of the dead in graves on an east-west axis displayed an awareness of space and the passage of time. For Voegelin, König’s work was confirmation of his theory of consciousness: consciousness was rooted in our place in the cosmos.

Cooper continues König’s and Voeglein’s work by looking at the archeologist Alexander Marshack who revolutionized the field of paleolithic art research. Being able to visit all over Europe to explore decorated caves, Marshack believed that human beings were not primarily toolmakers but symbol-makers and the creation of symbols was coeval with language. These symbols were part of a story that early humans needed for survival, reflecting the drama of ritual integration of societies with cosmic rhythms. Not only did these stories provided symbolic meaning in the cycle of birth and death and order and disorder but also had a pragmatic element of predicting when herds would pass by or fish would return.

Abbe Herni Breuil also contributed to our understanding of paleolithic art with his establishment of a chronological sequence of the decorated caves in southwest France that remained persuasive for many years. According to Breuil, the images found in the caves had an internal logic of their own and were related to hunting and fertility. However, as Cooper notes, Max Raphael, Annette Laming-Emperaire, and Andre Leori-Gourhan rejected Breuil’s argument that art evolved from simple abstraction to naturalistic complexity and instead viewed cave art as an ensemble of symbols instead of portraits of animals. These “mythograms” suggested that each cave was unique and contained a symbolic order existing within a complex context reflecting topography, region, and historical period.

Cooper then looks at the controversaries regarding the dating and the authenticity of cave art before discussing the shamanic hypothesis where chanting, music, and other ritual activities were related to cave paintings to fulfill a need for community and collective meaning. Competing theories were put forward to account for this hypothesis: Lewis-William’s and Dowson’s altered state of consciousness and Bahn’s and Helvenston’s three stages of trance. Cooper reviews the debates between these two accounts about what causes the shamanic experiences in cave art and how these theories eventually become academic ideologies that refuted evidence to the contrary.

However, which paleoscientist is correct matters less to Cooper than that each agree that neanderthal cave art is evidence of consciousness and the creation of such art reflects a sense of crisis. As Voegelin stated, “Anxiety is the response to the mystery of existence out of nothing. The search for order is the response to anxiety.”[1] The decorated caves is such an example and supports Voegelin’s theory of consciousness and his claim that original political order was cosmological.

Barry Cooper’s Paleolithic Politics is a thoughtful and thorough account of the Paleolithic period that brings unique insight into cave art and what it may mean for its authors and for us. If Cooper is correct, then political life did not begin with the Greeks but 25,000 prior and political theory therefore needs to be rethought and reconceived. For this reason, and for many others, is a reason to read Paleolithic Politics.

Notes

[1] Eric Voegelin, “Anxiety and Reason,” in What is History? And Other Late Unpublished Writings, ed. Thomas A. Hollweck and Paul Caringella (Baton Rouge, LA: Lousisiana State University Press, 1990), 71.