The Economy of Funerals and Aunts

The office of the Vice President, FDR’s second veep John Nance “Cactus Jack” Garner allegedly said, is not worth a bucket of warm spit. What do vice presidents do, after all, but go on endless diplomatic trips, especially the funerals of dignitaries foreign and domestic? “You die, I fly” was the lapidary phrase George H. W. Bush used to describe his work in Washington in that particular job.

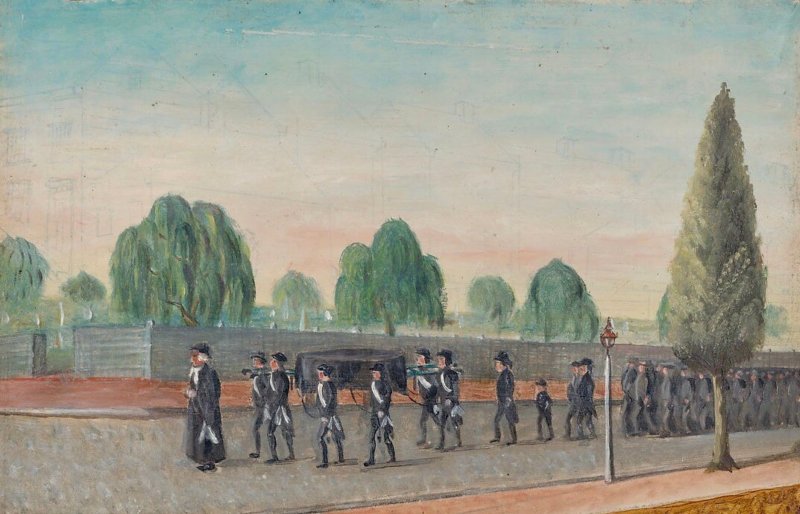

Whatever one’s conception of the vice presidency, traveling to funerals itself is certainly worth more than a bucket of warm spit. I would contend that in the case of our extended families, it’s actually an activity that we might all spend a bit more money and time on. Especially when one’s family is scattered to the four winds, as many modern families are, funerals become the times when one sees one’s relatives and actually gives a thought to both the dead and the living. Family funerals are the times when we look back on the lives of those who are connected to us by blood, which is to say, by the strangeness of Providence. God links us together with people to whom we are not necessarily related by common views, interests, or any of the other reasons a social media or dating service algorithm might use to link us. In short, we are related not by our own consent freely given.

Family funerals thus remind us of what it is easy to forget in an age in which we believe only the duties flowing out of our own choices are mandatory. We have duties to others that we did not consent to because we did not consent to be born in the first place, much less be born into the particular families we inhabit. Edmund Burke referred to such duties as “burdensome duties.” Burdensome they can be. Family is, as the saying has it, the place where they have to take you in when nobody else will. Family often can substitute for neighbors in Chesterton’s observation that the reason God tells us to love both our neighbors and our enemies is that they are so often the same people. “All my in-laws,” a t-shirt I once saw read, “are outlaws!” Even good relatives are like fish, as Poor Richard’s Almanac (via my Aunt Deane) had it: they both stink after three days.

But if family and their funerals remind us of the duties imposed by God and Tradition, they doubly remind us of the gratitude we owe God for putting us into a world with families that not only are not perfect but do not meet our own silly notions of what they should be. They include not merely people who are so bad we wouldn’t have chosen them, but also those so good in such different ways that we would never even have imagined them.

Such are the strange creatures known as aunts. While I’ve always appreciated Bertie Wooster’s collection of aunts, as I do all of Wodehouse’s creation, they pale in comparison to my own. Perhaps yours, too, if you think of them for a little while. I’ve been doing that a bit lately because the last two aunts on my mother’s side died within two months of each other.

Aunt Esther died in late September. I was not able to get to that funeral, which saddened me. Not related to me by blood but by the very wise choice of my late Uncle Blaine, Esther was—and a warning to those uncomfortable with technical philosophical language—a total babe. The photographic evidence shows that if I had known her in the bloom of youth I might never have had the nerve to talk to her. At one of their anniversary parties, Uncle Blaine proudly pointed everybody to a picture of his bride as a young bathing beauty. Wowza.

I feel vaguely guilty about saying this because of our modern preoccupations with equality and the denial of true things about the sexes. We must not be guilty of “looksism” or of reducing the worth of females to their external beauty. Of course I don’t believe her physical beauty made her worth more than others by virtue of itself. Nor do I think that her physical beauty was the most important thing about her. Instead, I point it out because in her case the exterior matched the interior personality. I never had the impression one gets with some of the pulchritudinously blessed that she either looked down on others not similarly advantaged or felt some sort of need to prove she wasn’t just another pretty face. Instead, she was who she was.

While Uncle Blaine was one of those hard-charging business executives who was always going and talking in such a way to render “a hundred miles a minute” an understatement, she seemed preternaturally calm. His way of loving people was to come up with a plan to solve your problem and then setting it in motion. It’s not that Aunt Esther wasn’t competent at solving problems or doing things. As a young woman she taught school in a one-roomed schoolhouse in Oakes, North Dakota. Throughout her life she volunteered for countless church and community activities, taught Sunday School for fifty-two years, and practiced a variety of crafts. She crocheted Christmas stockings specially designed with their first names for grandchildren, great-nephews and -nieces, and many others. All my children have an Aunt Esther stocking. Competence and indeed, well, craftiness were in her bag of tricks, too.

But her mode of dealing with problems was to see that you were having the problem and sympathize with you. Further, she knew what were real problems and what was simply an amusing mess. One of the memories that keeps coming back to me is being over at her house when I was about ten or eleven and helping her feed two of her grandchildren. The younger one was making the kind of mess that only highly-regarded abstract artists and toddlers at mealtime can create. I still see her in my mind’s eye sitting and smiling seraphically in the midst of flying oatmeal, taking in the mystery and joy of her progeny.

When Aunt Liz, the final aunt, died in November, five years to the day Uncle Lowell died, I determined not to miss it. She was just as pleased with her own family. Though she didn’t crochet stockings, she too kept track not only of her grandchildren but a good many of her grand-nephews, grand-nieces, and their birthdays. And as calming and exciting as Aunt Esther was, so charged with energy and fight was Aunt Liz. Seventeen years of age when she got married, she raised four boys and managed a very successful beauty parlor at the same time, cutting the hair of and befriending countless women all over the city of South Bend, Indiana. This friendship made it impossible for her rowdy boys to get away with anything away from home either, since she would hear about it before they even got home. And at home, though Uncle Lowell was the “chief referee” for my cousins, she wasn’t afraid to wade into the brawls. My cousin Tim in his eulogy told about her stepping into a dispute that involved a hot steam iron. “We ironed things out,” he deadpanned.

No, she was a fearless woman and a fighter, somebody who was not afraid of anybody or anything. Like Bertie Wooster’s Aunt Agatha, I do believe she might have eaten broken bottles for breakfast. My cousin Alan said of her, “You didn’t want her to fight your battles because things might get out of hand.” One of her progeny, a former major college baseball player, laughed as he told me how she came to a game one time and simply pushed past the policeman as she barreled into the dugout demanding, “Where’s my grandson?” The somewhat bewildered coaches simply pointed him out.

An old-school Democrat who both loved Jesus and could not stand Donald Trump (with Facebook page to prove it), she once said her only regret was having raised three Republicans. But though she held her views strongly, she didn’t let her politics get in between her and her family. One might think that while forgiving your own offspring’s political failings is one thing, that of your in-laws is another. Not in Liz’s book. One of her daughters-in-law is the kind of conservative who makes me feel wishy-washy occasionally. She was as close to Aunt Liz as any of them.

I’ve never been to a funeral where Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” was sung as a solo. Though I can’t approve of the practice, I can justify it only as her pastor did this out-there-but-characteristic request from the former organist. “Number one, you don’t say no to Liz and number two, her way was usually God’s way.” What marked out my aunt in the end was not her politics, but her faith and gratitude. Late in life she told her Methodist pastor, “We had a world war and a depression, but I had a great life.” And so she did.

Why spend the money on family funerals? What else are we going to spend our money on? For a few hundred dollars last month I saw cousins I hadn’t seen in years, prayed over my aunt’s body, heard stories that made me laugh and be grateful, and made me think again about how to be politically fierce without hating your own kin over it. That’s the kind of experience they can’t give you in Vegas or Cancun.

I may never be Vice President or even worth a bucket of warm spit, but my solemn vow to my family is renewed: if you die, and it’s possible, I’ll definitely fly.

This was originally published with the same title in The Imaginative Conservative on December 13, 2019.